Introduction

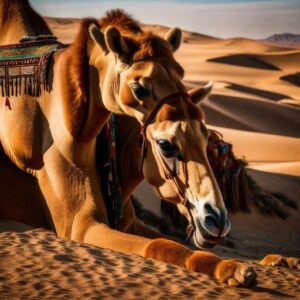

The Black Arabian Horse (Arabian breed), a graceful yet strong equine expression, has a long history dating back thousands of years. Evidence suggests it first appeared in Egypt around 1450 BCE and was immediately linked to light chariots. The Arabian horse breed has been closely studied in Saudi Arabia, with key examples dating from the 9th century BCE to the 4th century CE, based on co-occurrences with Ancient North Arabian inscriptions.

The idealized caricature of the Arabian horse created by the North Arabian artistic movement captured the main physical characteristics and body conformation criteria for the current breed. Archaeological remains, such as size overall, a dished rostrum on the skull, or a missing lumbar vertebra, are the preferred method of identifying Arabian horses. However, large-scale metric assessments are challenging in the Near East due to limited sample numbers and fragmented bones.

Colour and conformation of Arabian horses(Black Arabian Horse)

The black arabian horse (Arabian breed), characterized by its adaptable characteristics, has evolved in dry environments. Today’s Arabian horses come in various colors and have black skin for protection. Some horses have markings like sabino or rabicano, but breeders consider too much white to be “bad medicine.” Khalil Rizkallah al-Khuri, as narrated by Shaikh Isa al-Uqaidi, discusses the good and evil omens associated with color marks in his book, The Good and Evil Signs of Horses.

The black arabian horse is renowned for its extraordinary endurance and elegance. With a light build, Arabian horses stand between 142 and 157 cm tall, featuring a unique jibbah, a bulge on the frontal bone that increases the frontal area of the brain and includes sinuses to regulate hot, dry air. The Arabian breed’s unique bridles, featuring smaller bits, contribute to its extraordinary endurance. The Arabian breed’s unique conformation, including a concave facial profile and a broad forehead, contributes to its unique appeal.

The ideal Arabian horse should have a powerful arched neck, positioned high with the head bent downward, allowing for improved collection and quick bursts. The throatlatch, where the head and neck meet, should have enough space for the windpipe, ensuring a well-set windpipe deposit. The withers should be high and placed far back into the neck.

Arabians are short-coupled, with a back shorter than its belly and an underline of 1:2. They have 18 thoracic, 6 lumbar, and 5 sacral vertebrae, and a deep chest and well-sprung ribs for the highest lung capacity. The croup is a distinctive trait of Arabians, with a horizontal hip angle and a higher tail carriage. An elevated tail, or “flagged” tail, helps keep the animal cool while moving. These traits contribute to the Arabian’s unique characteristics and performance in hot, arid climates.

The introduction of horses and wheels to Arabia

The oldest evidence of domesticated horses and the chariot (or potentially the cart) in the Arabian Peninsula can be found in northern Saudi Arabia as schematic images in rock art. There are currently many instances of two horses hauling a small two-wheeled vehicle, and these instances match those seen throughout Eurasia in places like Scandinavia10, Mongolia11, Central Asia12, and North Africa13. The stereotypical Arabian pictures feature two recumbent horses, typically placed back to back, with a draught pole in the middle of them that is attached to the chariot box or cart.

The two wheels are flattened out to the sides of the chariot or cart and contain four spokes apiece.

These geographically widespread symbols, which are often dated to the Late Bronze Age/Early Iron Age, or to the latter part of the 2nd to the early 1st century BCE, may provide information on when domesticated horses first arrived in Arabia.

Given that this stylized form of depictions is so common throughout the entire Eurasian steppes, where donkeys were unknown and horses were buried with chariots rather than carts, it should be made clear that the author firmly believes these images depict horses and chariots, rather than donkeys and carts.

The Artists Who Created the North Arabian Horse Petroglyphs

The frankincense and myrrh trade brought prosperity to the inhabitants of these northern Arabian oasis in the first millennium BCE, but according to charcoal samples, the community at Taym Oasis was already encircled by a 15-km wall by the 19th–18th century BCE.16 Prominent villages built around important wells, like Bir Haddaj at Taym, show the wealth created by camel caravans that brought the priceless incense products up from the south to be dispersed to even farther-off areas and civilizations.

With a few notable exceptions, the petroglyphs appear to have been created by the locals, who are primarily nomadic herders, based on the subject matter. Most of the time, the inscriptions found alongside petroglyphs in the area near Taym consist of a person’s name (likely the author’s signature), however a few are prayers or list the many kinds of animals that are shown.

Ancient North Arabian graffiti often includes inscriptions and depictions of Arabian horses and camels. In the area surrounding Taym, hundreds of pieces of graffiti painted on cliff sides offer some, if limited, insight into the people who left their markings.

Although there was minimal standardisation in the letter arrangement and the most of the inscriptions are single or extremely short words, the nomads did possess some literacy.17 The accompanying visuals emphasise the enormous significance they place on their domesticated animals, especially horses and camels.

Yariris, a Hittite regent of the city of Carchemish, made a reference to ancient Taymanitic writing about 800 BCE. This gives us an idea of how old that regional script is. The mention of the Neo-Babylonian King Nabonidus, who ruled Taym for 10 years during the Dynasty XI or Chaldean Dynasty (556–539 BCE), gives us the oldest known date for writing in the Taym territory proper. A few decades after Nabonidus introduced Aramaic in the oasis communities itself, the use of this writing appears to have decreased.

Thamudic B, C, or D rather than Taymanitic is the predominant writing style used in the graffiti linked with petroglyphs, which was most likely created by nomads who lived outside the community. On a tomb in Madain Li (also known in ancient times as the Nabataean appellation Hijra or as Hegra in Greek and Latin), Thamudic D was preserved at least until the third century CE. Thamudic B is the script used in the great majority of inscriptions.

The North Arabian School of Art

Sandstone surfaces from the first millennium BCE to the first few centuries later depicted horses (black arabian horse) and camels in regional styles. These animals, often prominent in the center of petroglyph panels, were characterized by a long, downward-sloping neck, a semi-circular hump, and vertical forelimbs. The distinctive elements of the North Arabian design include a big eye, drooping lip, pointed ears, and a pinched loin with a tufted tail.

Horses (black arabian horse) exhibit Arabian traits such as a short nose, concave facial profile, huge eye, tiny ears, and a twisted rear. This distinctive “biangular” method of presenting horses is more common in North Arabian art than wild animals like ibexes. The style’s geographical span is most concentrated around Taym, extending to Jubbah and Il, and al-Ul.

Horses’ Treatment in the North Arabian Petroglyphs

Black Arabian horses were kept, trained, groomed, ridden, used to draw chariots, served in the military, and more. This study’s analysis of petroglyphs reveals a wealth of information on these practises. Therefore, despite the dearth of archaeological horse bone evidence to date, Arabian rock art can help us understand the functions and care that horses served. This evidence shows that in addition to being valuable as a mode of transportation, Arabian horses were also prized and kept as status symbols.

Horse Training

Understanding the care, handling, and training of early black Arabian horses may be gained through studying Arabian rock art. Al-Nalah, a location 47 km south of the oasis of Taym, is the greatest location to observe horse training.By holding a lead that is tautly fastened to the horse’s halter with his left hand, the guy in this image maintains the horse’s head in the proper posture. He is holding an arrow, tip up, vertically in his right hand. The projectile is out in front of the horse in its line of sight, maybe to function as a goad or a contemporary halter whip during training to persuade the horse to focus.

Tack

This collection of petroglyphs depicts various pieces of equipment, such as bridles and halters, riding crops, saddle blankets, harnesses on chariot horses, and maybe caparisons or pieces of armour on one chariot horse’s neck and breast. Lack of stirrups and saddles is expected considering that they are not necessary and may have even been unheard of in the area at the time.

The first saddles that have been found date to the 8th century BCE in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of Northwest China; however, it wasn’t until the 400–200 BCE period or even later that saddles spread to other areas. Unless engaging in hand-to-hand combat on horseback or using thrusting weapons while mounted, several tribes opted not to wear the saddle. Stirrups are much later, first appearing in the first century.

Unless engaging in hand-to-hand combat on horseback or using thrusting weapons while mounted, several tribes opted not to wear the saddle. Stirrups are much more recent, emerging in India only in the first century BCE or first century CE.

Tribal Markings in Brands

Bedouin people brand their cattle with wasms, which are also used to mark tribe and territorial borders on stones, cliff sides, and livestock. They also functioned as burial markers, a signature on paperwork, and a way to show that a tribe member had been in a certain location. These have been used for millennia and, in some cases, have been recycled by contemporary Bedouins. They are rather straightforward geometric patterns. They signify livestock ownership and illustrate branding when they are depicted in the rock art on domesticated animals like horses or camels. Examples have been discovered on a couple of the horses, with al-Nalah being the finest specimen.

Shading on the Horse

Rock art depicts Black Arabian horses with lighter-colored surfaces, revealing darker zones on their bodies. These horse representations can be interpreted in various ways, including pelage color patterns, which are common in Arabian petroglyphs. The leg zones are solid and end at the same level on the left and right sides of the animal’s limbs. Leg wraps may be the cause of the darker areas on the feet, as they support the horse and prevent cannons’ delicate skin from being scraped by the opposing foot’s hoof or foliage. Modern leg wraps are often limited to cannon bones, as seen in Persian illuminations from the 16th century.

Grooming

Black Arabian horse rock art depicts horses with various grooming techniques, including upright manes, roached manes, and tangled tails. These techniques are beneficial for equestrian archers and chariot horses, as long, flowing manes can tangle with the reins. In ancient and modern cultures, such as Egyptian, Assyrian, Persian, Chinese, and Etruscan, changing manes is common. Tails are also handled differently, with some tasselled tails indicating an ass or onager. Short hair covers the sides of the dock on zebras, asses, and onagers, while long hair forms a tassel halfway down the tail. Petroglyphs in Arabia depict older, Neolithic onagers or African wild asses, indicating their distinct bodily conformations.

Conclusions

In conclusion the North Arabian artistic movement, originating in Taym Oasis, produced petroglyphs of black Arabian horses and camels between the first millennium BCE and the early first century CE. These depictions of horses and camels, essential for transportation and prized possessions, were prominently emphasized on caravan routes and oases during the incense trade boom. The Arabian breed’s social status is evident in the well-groomed animals, henna, and training illustrations. The military functions of horses in chariot warfare and cavalry are also evident in these petroglyph panels.